I recently finished reading Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals, a compelling look at meat consumption, the rise and dominance of factory farming, and animal cruelty, among other things. This was shortly after completing Whole: Rethinking the Science of Nutrition by T. Colin Campbell and Howard Jacobson that talks about the benefits of a whole food, plant-based diet and some of the problems with the science of nutrition as is practised today. So this post is mainly some thoughts, questions and dilemmas I’ve had on the subject of animals as food.

A quick disclaimer: Although I have never been a total vegetarian or vegan (and I am not sure we even need to go into that binary in order to make a difference in the world), I have steered my cooking habits to more plant-based meals over the years.

The planet and efficiency

Eating an animal is inherently inefficient. If I were to turn vegan someday, this would be my top reason. Like walking or cycling to buy a loaf of bread rather than driving a Ford F150, consuming grain and vegetables directly is less energy intensive than consuming animals that consume grain and vegetables. No matter how economical meat and dairy are (and this is something I’ll get into later), the added layer of consumption simply takes more resources from the planet, usually robbing them from people who are not in a position to object. Besides, considering the state of the climate world over, we need to decide whether we want our beef burgers and chicken wings now or a habitable future (a test of short term versus long term gratification).

Cruelty

This is a more nuanced issue that I don’t fully grasp to take a stand on. While on one hand, you can argue that nature has a lot of cruelty and animals rarely die honourable deaths in the wild; on the other, you have factory farms where humans manufacture, kill and package other animals into neat little unrecyclable styrofoam containers with little regard for their rights.

However, there’s more to cruelty. For instance, as I recently learnt from Eating Animals, in fishing, a large proportion of a catch, called the bycatch, is simply written off as collateral damage. Simply so that you can have your Omega-filled wild salmon.

Another way to look at this could be: If we were to not incentivise factory farming, and subsidise animal protein, would it not be depriving the poor and thereby cruel to them?

The cruelty point is also something I’ve seen vegetarian Indian savarnas (or privileged caste, primarily Hindu folks) using to defend their beliefs. Ironically, these very people still consume milk and dairy products which are derived from keeping cattle lactating for years, which is also a form of slavery.

Keeping animals vs. eating them

The cruelty debate also brings up the dichotomy of pets and what animals we choose to befriend or eat. For instance, you may be okay with getting a Border Collie to keep your furniture company when you’re at work, but not consuming (other) dogs (even Chihuahuas). Foer brings this up in the book as a sliding scale with say dogs on one end of the spectrum (for loving, not eating), and fish on the other (for eating). The cast of creatures on this scale changes for each society. For many savarnas, cows fall somewhere close to dogs, except they (the savarnas) have a free pass when it comes to enslaving/domesticating them and consuming their milk.

Other questions around this dichotomy include: Can you claim to love animals while also eating them or their products? Is it even ethical to keep and raise another animal for food? In fact, is it humane to keep an animal, whether they are meant for food, companionship or security?

The caste connection

In India and other parts of South Asia, meat consumption is closely tied to the caste system. At present, savarnas tend to glorify vegetarianism.

However, this was not the case historically and in fact, it even used to be the other way around: savarnas favoured meat consumption, and animal sacrifice was prevalent in several religious ceremonies. Hence, in many communities, meat consumption is considered anathema (while dairy consumption is not), and people who do – like Muslims, Dalits, etc. – are othered.

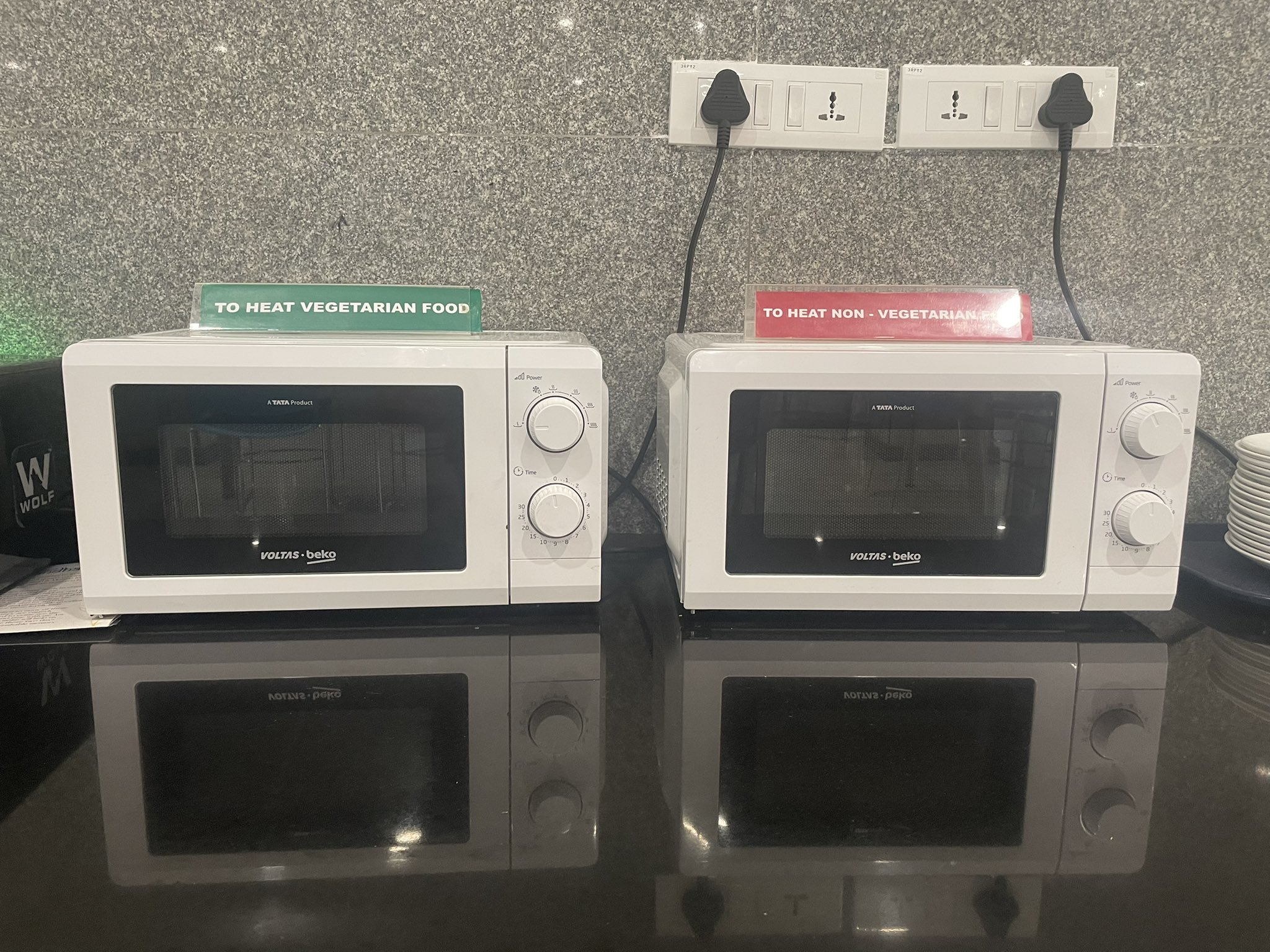

However, it’s not black and white, as things change considerably geographically, and with urbanisation and class mobility. Well-off urban savarnas will wax poetic about beef burgers but not include it in their caste-dominated rituals like weddings. The idea of inferior and superior, of pure and impure, that stems from the caste system, lends itself to meat eating. Politically correct casteist savarnas consider meat eaters “impure” but instead of using the caste argument to label them that, will use cruelty and animal rights to defend vegetarianism. This then translates into segregation practices including separate utensils for cooking meat or even reheating food like “veg microwaves”, segregated dining areas, and pressure on restaurants to ensure meat is handled and prepared away from vegetarian dishes (the latter also betrays another Indian deficiency: rationality and scientific temper in everyday life).

For more about caste and veganism/vegetarianism, please check out this article by Bijaya Biswal on the Feminism in India portal.

Economics and nutrition

Some parts of the previous discussion have revolved around moral questions but if you are poor, things often boil down to economics. And in the Western world, eating meat might actually be more affordable. Foer explains in the book that our current policies make meat cheaper than it actually is. The cost also discounts other factors like the pollution caused by the industry, the dangers of animal monocultures, and any cruelty involved in animal husbandry. If meat prices are controlled so that we have cheap animal protein, this brings me to another question: Are we really suffering health problems by not eating adequate amounts of protein? Is the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of protein exaggerated? I am yet to explore the science behind this so please do your due diligence before giving up your brotein cadre membership.Beyond the binary, and transitioning

For anyone who can afford it, the logical conclusion to this debate is to go vegan. But over the years I have come to understand that our thinking cannot be so binary, and solutions to many issues can be spread out on a spectrum. So too with this debate, perhaps you need not undertake a total modeshift in your eating habits. Maybe you can be vegan for 60 percent of the time, vegetarian for 30, and omnivore for the remaining 10 percent. For my part, I am trying to only cook vegan or vegetarian meals at home, and to leave my meat consumption to when I am eating out, which is once a week or less. The trick, as I tried with intermittent fasting, is finding a sustainable solution. Transitioning at a pace and arriving at a plant-to-meat ratio that works for you ensures you don’t find the lifestyle change to be massive, and revert to your previous eating habits.Individual choices vs. influencing more people

Finally, you may also have this question: Is my decision going to make any meaningful difference in the world? This is something people the world over and in different epochs have asked (both themselves and bearers of new ideas), for a wide range of matters, and while I don’t have an empirical answer, I feel you must believe that it does and do it. Then, if you feel like doing more, expound your ideas. There is of course the risk of turning into an evangelical vegan who goes around proselytising. Perhaps, here too there is a middle ground, and you can decide whether and how you want to spread the message.Congrats, you made it to the end. That could not have been a quick read (unless you’re a bot or a search engine spider). Consider rewarding yourself with a cold beer and some fries to undo the damage. I will try and keep the next one short.