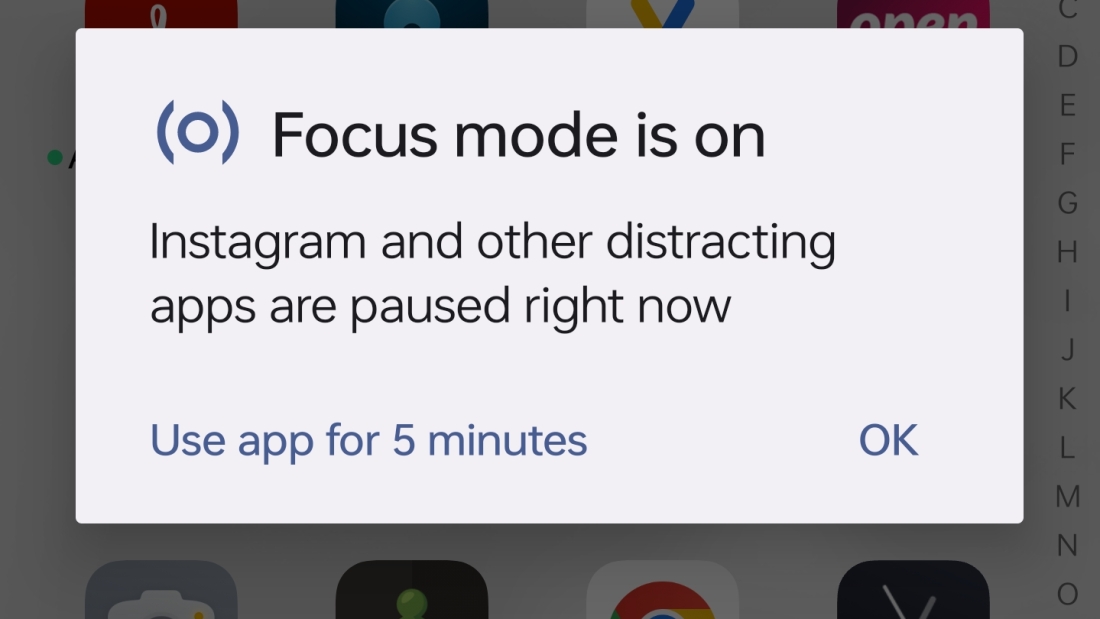

Got troubles with screen time? Here’s how I use Focus Mode, intermittent fasting & other steps to tackle the problem & have digital wellbeing.

Eating animals

An essay on the dilemma of meat consumption, touching on climate change, ethics, caste, etc., based on the books I’ve recently read.

5 years of Intermittent Fasting and how I do it

My multi-year experiment with intermittent fasting or time restricted eating, with notes on the personal changes I’ve observed.

Hostels and the sense of enough

A take on living in hostels as a digital nomad, and the charms of living with fewer material possessions in general.